Beef tallow has made a strong comeback in kitchens across the United States. This traditional cooking fat, once pushed aside during the low-fat diet craze of the 1980s and 1990s, now appears on restaurant menus and home pantries. The shift reflects growing interest in traditional food preparation methods and natural cooking fats.

Rendering beef tallow at home costs less than buying it ready-made and gives you complete control over quality. A pound of beef suet typically costs $2 to $4 from a butcher, while pre-rendered tallow sells for $8 to $15 per pound in specialty stores. The process itself requires minimal equipment and surprisingly little active cooking time.

Understanding Beef Tallow and Its Uses

Beef tallow is rendered fat from cattle, primarily from the suet found around the kidneys and loins. This internal fat has a higher melting point than other beef fats, making it stable at room temperature and excellent for high-heat cooking.

The fat contains primarily saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids. Its smoke point reaches approximately 400°F, which makes it suitable for frying, roasting, and sautéing. Many restaurants now use tallow for french fries because it creates a crispy exterior while adding rich flavor.

Beyond cooking, people use rendered tallow for soap making, candle production, and skin care products. The fat’s composition closely matches human sebum, which explains its traditional use in balms and moisturizers.

Getting Started: Equipment and Ingredients

The rendering process requires basic kitchen equipment you probably already own. You’ll need:

- A large stockpot, slow cooker, or Dutch oven

- Sharp knife or food processor

- Fine mesh strainer or cheesecloth

- Storage containers (glass jars work best)

- Wooden spoon for stirring

For ingredients, you only need one thing: beef suet. Most butchers sell suet for a low price or give it away free to regular customers. Some grocery stores with butcher counters also stock it, though you may need to call ahead and request it.

Quality matters. Grass-fed beef produces tallow with a different nutrient profile than grain-fed beef, including higher levels of omega-3 fatty acids and conjugated linoleic acid. But either type works fine for rendering.

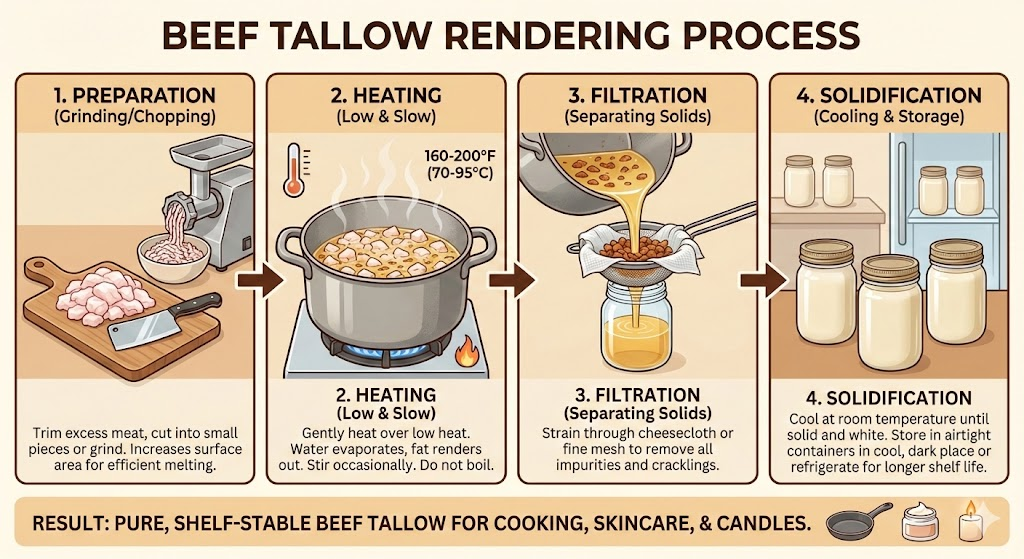

Preparing the Suet

Start by examining your suet. You’ll notice chunks of white fat mixed with some membrane and possibly small bits of meat. Don’t worry about removing every tiny piece of membrane, but trim away any large sections of meat or connective tissue.

Cut the suet into small pieces, roughly one-inch cubes. Smaller pieces render faster because they expose more surface area to heat. Some cooks freeze the suet for 30 minutes before cutting to make it easier to handle.

A food processor speeds up this step considerably. Pulse the cold suet until it reaches a ground beef consistency. Just avoid over-processing it into a paste.

The Wet Rendering Method

Two main methods exist for rendering tallow: wet and dry. Wet rendering involves adding water to the pot, which prevents burning and makes the process more forgiving for beginners.

Place your cut suet in a large pot and add water to cover about one-third of the fat. Turn the heat to medium-low. The water will prevent the fat from scorching as it begins to melt.

As the mixture heats, the fat will liquefy and separate from the solid tissue. Stir occasionally to prevent sticking. The process takes 3 to 6 hours depending on the amount of suet and your heat level.

You’ll know rendering is complete when the liquid turns clear and golden, and the solid bits (called cracklings) turn brown and sink to the bottom. The water will evaporate during cooking, leaving pure fat behind.

Once finished, strain the liquid through cheesecloth or a fine mesh strainer into clean glass jars. Work carefully because the fat is extremely hot. Some cooks strain twice for extra-pure tallow.

The Dry Rendering Method

Dry rendering requires no water and produces tallow with a slightly richer, beefier flavor. This method demands more attention to prevent burning.

Place the suet pieces in your pot without any liquid. Set the heat to low, seriously low. The fat should melt slowly and gently. High heat creates a burnt taste and darker color.

Stir more frequently with dry rendering, especially at the beginning. As fat accumulates in the pot, the risk of burning decreases. But keep checking every 15 to 20 minutes.

The cracklings will float at first, then gradually sink as they release their fat. Total time runs 4 to 8 hours. Using a slow cooker on low heat setting works perfectly for dry rendering and requires less monitoring.

When the cracklings turn golden brown and crispy, and the liquid fat looks clear, you’re done. Strain the same way as wet rendering.

Slow Cooker vs. Stovetop vs. Oven

Each heating method has advantages. Slow cookers provide consistent low heat and require minimal supervision. Set it on low in the morning and check it in the afternoon.

Stovetop rendering gives you more control over temperature but needs more attention. It’s faster than a slow cooker but carries higher risk of burning.

Oven rendering splits the difference. Place your pot in a 250°F oven and check every hour. This method distributes heat evenly and reduces hands-on time while preventing scorching.

Storing Your Rendered Tallow

Properly rendered and stored tallow lasts for months at room temperature or over a year in the refrigerator. The key is keeping it free from moisture and food particles.

Glass jars with tight-fitting lids work better than plastic containers. Mason jars in pint or quart sizes handle the hot fat safely and seal well.

The tallow will be liquid when you pour it into jars. As it cools, it solidifies into a creamy white or pale yellow fat. Any impurities or water will settle at the bottom. If you notice a layer of liquid under your solid tallow after a day or two, carefully pour off the solid portion and discard the liquid.

Label your jars with the rendering date. Store in a cool, dark place like a pantry, or refrigerate for extended shelf life. Freezing works too if you have the space.

Signs of spoiled tallow include off odors, mold growth, or a rancid smell. Properly rendered tallow should smell clean and slightly beefy, not unpleasant.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Burning the fat ranks as the most frequent error. Once tallow burns, there’s no fixing the bitter taste. Always use low heat and stir regularly.

Incomplete straining leaves particles that can cause spoilage. Strain through multiple layers of cheesecloth or a very fine strainer. Some people strain hot, let the tallow solidify, then remelt and strain again for crystal-clear results.

Adding meat scraps or non-fat tissues to your rendering batch introduces protein that can spoil. Stick to pure fat for the longest shelf life and best quality.

Rushing the process with high heat might save time but ruins the final product. Low and slow wins every time with tallow rendering.

Using Your Rendered Tallow

Tallow shines for high-heat cooking applications. Use it for:

- Pan-frying and deep-frying - The high smoke point makes it perfect for chicken, fish, or vegetables

- Roasting vegetables - Toss potatoes, carrots, or brussels sprouts in melted tallow before roasting

- Pie crusts - Replace butter or shortening with tallow for a flaky, tender crust

- Sautéing - Use in place of oil or butter for meats and vegetables

- Seasoning cast iron - Tallow creates an excellent non-stick coating on cast iron cookware

The flavor profile works best with savory dishes. While you can use it in baking, the subtle beef taste might not suit all recipes.

For cooking, scoop out the amount you need and melt it in your pan. It liquefies quickly over medium heat. One tablespoon of solid tallow equals about one tablespoon of liquid oil.

Cost Savings and Sustainability

Rendering your own tallow makes financial sense. The typical yield is about 75% to 80% rendered fat from raw suet. Two pounds of suet at $3 per pound gives you roughly 1.5 pounds of tallow for $6, compared to $12 to $22 for store-bought.

The practice also reduces food waste. Butchers often discard suet or sell it as pet food because few consumers request it. By rendering at home, you’re using a part of the animal that might otherwise go to waste.

Many people who buy whole or half cows direct from farms accumulate suet they don’t know how to use. Rendering converts this overlooked cut into a valuable cooking fat.

Nutritional Considerations

Beef tallow contains approximately 115 calories per tablespoon, similar to other cooking fats. The fatty acid profile includes about 50% saturated fat, 42% monounsaturated fat, and 4% polyunsaturated fat.

The saturated fat content once made tallow controversial. Current nutrition science takes a more nuanced view of saturated fats, recognizing that not all saturated fats affect health identically. Tallow from grass-fed beef contains vitamins A, D, E, and K in their fat-soluble forms.

As with any cooking fat, moderation matters. Tallow works as part of a varied diet that includes multiple fat sources.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Sometimes rendered tallow develops an off-white or grayish color instead of pure white. This usually results from impurities or burnt bits. The tallow remains safe to use but may have a stronger flavor. Better straining prevents this.

A greasy or slimy texture when solid indicates incomplete rendering or water contamination. Remelt the tallow, bring it to a gentle simmer to evaporate any water, and strain again.

If your tallow smells too strongly of beef, you can make it milder. Melt the strained tallow with a few cups of water, stir well, then refrigerate overnight. The tallow will solidify on top while impurities sink into the water below. Lift off the solid tallow and discard the water.

Making the Most of Cracklings

Don’t throw away those crispy brown bits left after straining. Cracklings are delicious. Salt them lightly and eat as a snack, similar to pork rinds. Or chop them and add to cornbread batter, biscuits, or savory pastries.

Cracklings spoil faster than pure tallow because they contain protein. Store them in the refrigerator and use within a few days, or freeze for longer storage.

Some people leave a few cracklings in their tallow for added flavor. This shortens shelf life slightly but creates a more robust taste.

Getting Started Today

Rendering beef tallow requires patience more than skill. The process is straightforward: cut fat into small pieces, apply gentle heat for several hours, and strain out the solids. No special techniques or expensive equipment needed.

Start with a small batch of two to three pounds of suet. This gives you enough rendered tallow to experiment with cooking applications without overwhelming your storage space. Once you see how easy and economical the process is, you can scale up.

Call local butchers this week to ask about suet availability and pricing. Many will save it for you if you place a regular order. Some farmers’ markets also sell suet, particularly vendors who sell whole animals or custom cuts.

The revival of traditional cooking fats reflects broader interest in food quality, sustainability, and connections to culinary heritage. Rendering your own tallow puts you in direct contact with your food sources and gives you a versatile, economical cooking fat that performs beautifully in the kitchen.

Further reading

- How to Store Beef Tallow (Shelf Life, Refrigeration, Freezing)

- How to Use Beef Tallow in Homemade Soaps and Balms

- Is Beef Tallow Good for Keto and Carnivore Diets?

- Is Beef Tallow Healthy? What Nutrition Science Says

- What Makes Beef Tallow Worth Using in Your Kitchen

- What Is Beef Tallow? A Simple Guide for Beginners

- Where to Buy High-Quality Beef Tallow (Online & Local Options)